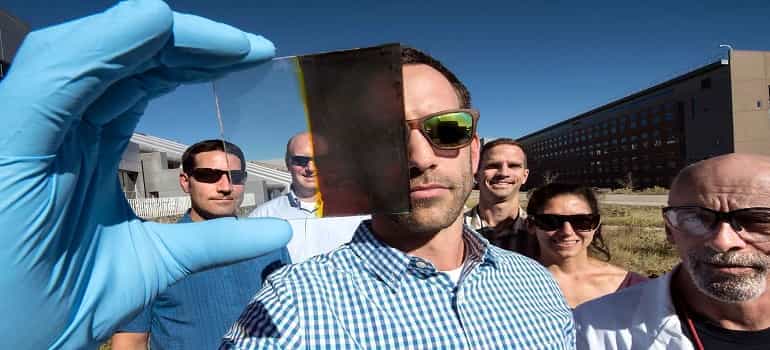

An international research team has created a flexible solar cell that could revolutionise future wearable technology.

An ultralight flexible solar cell, 10 times thinner than the width of a human hair, could hold the key to promising power sources for future wearable technology.

In a pair of research papers, published in the prestigious journals Joule and PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA), an international research team, involving Monash University, has developed a super-thin photovoltaic cell that has high efficiency, supreme mechanical bending and stretching capacity, and capabilities to provide a long-lasting power source.

In the Joule paper, researchers successfully developed novel mechanically robust photo-absorber materials that can make ultra-flexible solar cells. These cells can achieve a power conversion efficiency of 13 per cent with 97 per cent efficiency retention after 1000 bending cycles, and 89 per cent efficiency retention after 1000 stretching cycles.

“Power conversion efficiency considers how much solar energy can be converted into electricity. The solar energy illuminated on Earth is 1000 watts per square metre. Our device can produce 130 watts of electricity per square metre. The 13 per cent efficiency we were able to achieve is one of the highest efficiencies in organic solar cells,” Dr Wenchao Huang, Research Fellow in Monash University’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, said.

In the PNAS paper, tests have shown that when this solar cell was treated with a special method, its performance had only dropped 4.8 per cent after a staggering 4736 hours; could run for more than 20,000 hours – about 2.5 years – with minimal degradation, and had an estimated shelf life of 11.5 years.

At a size of just 2cm squared – roughly the same as an Australian 5c piece – this solar cell is light enough to be supported by a flower petal and can generate 9.9 watts of power per gram.

With further testing, this revolutionary device could be used as a replacement for batteries in a number of future technologies such as mobile phones, watches, internet of things (IoT), and in biosensors.

Researchers at RIKEN in Japan, with collaborators from The University of Tokyo, The University of California, the Australian Synchrotron and Monash University, led these studies. Researchers are now working to commercialise this technology.

“Currently, silicon solar cells are the dominant technology in the photovoltaic market, which are commonly found in rooftop installations. But, their brittle nature means solar cells exhibit poor performance when bent or stretched,” Dr Huang said.

“Here, we have developed an ultra-flexible organic solar cell with a total thickness of just three micrometres – one of the thinnest solar cells in the world.

“Our ultra-flexible solar cells can simultaneously achieve an improved power conversion efficiency, excellent mechanical properties and robust stability. This makes them a very promising candidate as a power source in wearable electronics to realise long-term monitoring of various physiological signals, such as heart and breathing rates.”

Researchers developed new materials and a simple post-annealing method to improve the mechanical and environmental stability of the organic photovoltaic, without inefficiency, to improve stability and scalability. Annealing is a heat treatment that alters the physical, and sometimes chemical properties, of a material to reduce its degradation.

These solar cells were fabricated and tested in a laboratory in Japan with advanced thin-film deposition and characterisation equipment. Some crucial parts of this research regarding device physics were conducted in the Renewable Energy Laboratory at Monash University and the Australian Synchrotron.

Despite its size, these low-cost solar cells can be reproduced easily with continuous printing technology, which makes them ideal for the fast tracking and mass production of wearable technology.